| |

Taken from The Atlantic (Jul 24, 2020)

The Funkadelic Album That Predicted the Future

The legendary band could almost blend in with other acts during the counterculture of the '70s. But today, the group looks like a pure phenomenon.

by James Parker

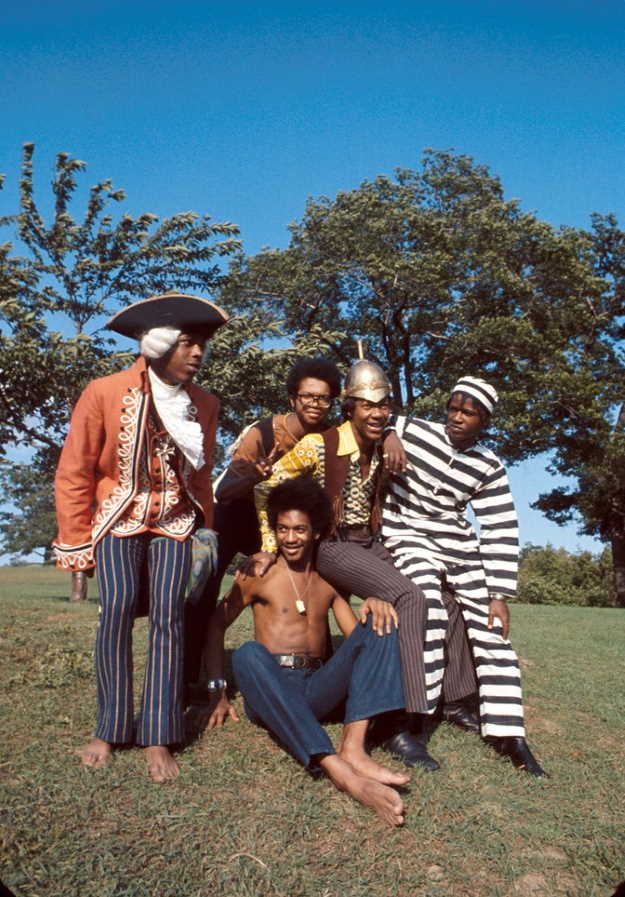

Funkadelic had a split-level reality-and the insights granted thereby-as their birthright. Michael Ochs Archives / Getty |

Fifty years: a breath. A snap of the fingers. Or in the case of Funkadelic's Free Your Mind ... And Your Ass Will Follow-recorded in one day, with the whole band tripping on LSD-a single ageless lizard-blink of the third eye.

Is it possible that this album sounds heavier and crazier today than it did upon its release in July 1970? I think it's very possible. In the general countercultural churn of the '60s becoming the '70s, after all, and in Funkadelic's home base of Detroit in particular (where they regularly played with the MC5 and the Stooges), a carnivalesque Black ensemble that produced ghostly, searing acid rock with Motown-level chops and head-spinning street-surreal lyrics could just about-just about-blend in. But not now. Seen from here, from this summer, Funkadelic looks like a pure phenomenon: a superb and lonely plume of emancipatory energy.

The stuff about recording Free Your Mind in one day on LSD is, as with much Funkadelic history, apocryphal. Or unverified. Or cloaked in a drug miasma. I prefer apocryphal, because it gets at the lost-gospel, extracanonical quality of this music. Free Your Mind was the second in Funkadelic's great triptych of early albums for the Westbound Records label. The first, Funkadelic, was released earlier that year, and Maggot Brain would follow in 1971. All three records seem to float outside rock and roll, hovering there, levitating in fields of esoteric knowledge.

An aspect of that knowledge, of course, was Blackness: being Black-flamboyantly, psychedelically Black-in an America that, through the madly flexing prism of the '60s, was only beginning to experience itself. The white rebel rock bands, as outré as they might have been, were not privy to this knowledge. So the MC5 could rave about revolution and mind expansion, but Funkadelic had a split-level reality-and the insights granted thereby-as their birthright.

Members of the band pose for a portrait in September 1969. (Michael Ochs Archives / Getty) |

Also, they were geniuses. George Clinton, the band's front man, was mastermind, wizard, and chief storyteller of a prodigious musical collective that also included his old New Jersey barbershop quintet, the Parliaments. Clinton was better than an anarchist; he was an exploded formalist. He came out of Tin Pan Alley, having spent much of the '60s doing production-line songwriting for Motown. He took so much acid, according to him, that it eventually stopped working. His head was selectively shaved in a proto-punk tonsure. His imagination was bottomless, his sense of humor grotesque. Another shard of apocrypha from the same era has Funkadelic plotting a joint album with the hard-rock dirge-mongers Iron Butterfly. It was to be called Heavy Funk, with a 400-pound white woman on the front cover and a 380-pound Black man on the back.

The Funkadelics, wild as they appeared and sounded, drug-deranged as they undoubtedly were, were professionals: virtuosic session men, with serious musical profiles. Tradition was their secret weapon: Embedded in the Funkadelic freakout-parodically sometimes, spookily sometimes-were doo-wop harmonies, gospel calls, Temptations-style dance routines, writhings of soul. Eddie Hazel, on lead guitar, combined Hendrixian technique (and wah-wah pedal) with an electric fragility or exposure that was all his own. "He just felt everything," Clinton said simply in an interview published in 1994, two years after the guitarist's death.

Hazel played like he had conjured himself a nervous system out of deep feedback. He shivered. He howled. His weeping, melting flights were sustained, sponsored, guaranteed by the hulking funk undercarriage of Tawl Ross (rhythm guitar), "Billy Bass" Nelson, and Tiki Fulwood (soon to be pinched by Miles Davis) on drums. And then there were the keyboards of Bernie Worrell, who had come to Funkadelic via Juilliard and the New England Conservatory of Music. Of the Westbound albums, Free Your Mind belongs particularly to Worrell and his RMI Electra Piano. In the blisteringly distorted chords that he plays on the title track, and in the cracked-piano musings that he sprinkles over "Funky Dollar Bill," the band seems to be dosing itself with blasts of European avant-gardism.

Free Your Mind certainly sounds like it was recorded in one day on LSD. Clinton, in the producer's chair, forced an ad hoc astral marriage between England's Joe Meek, the cracked architect of the Space Age smash "Telstar," and Jamaica's muttering dub innovator Lee Perry. The high end fizzes unstably; there are vicious, whimsical side-to-side pannings and plunges into reverb, creaky sci-fi noises, chemtrails everywhere, sonic snake tails, moments of chaos, and supernatural moments of coalescence. Behind the songs, receding into mystery, is an entire spectral dimension of echo and shimmer and hiss. From this dimension emerges the heavy funk, the grooves that lumber hugely and almost metallically into being and then dematerialize, back into the ghost world. Nothing had ever sounded like this-nor would it again. Had the whole troupe detonated and disappeared after this record, it would have only been appropriate. But it didn't, as we know: Huge chapters of expansion and evolution awaited Clinton and his Parliaments/Funkadelics.

George Clinton at Central Park SummerStage in New York in 1996. (Jack Vartoogian / Getty) |

"Free your mind and your ass will follow!" exhorts a preacher-ish Funkadelic at the beginning of the album-to which a hypnotized-sounding chorus of female voices offers the response: "The kingdom of heaven is within!" Within, within-that's where the heavy funk goes: into biology, into the body. Transcendence via immersion. "Look out here I come," sings another Funkadelic, in Freudian mood, on "I Wanna Know If It's Good to You?," "right back where I started from." And what is it that needs to be transcended? Capital, racism, the system, the whole thing. "The pusher push, the fixer fix, the judge acquits, the junky leads his life ... for the dollar bill" ("Funky Dollar Bill"). Funkadelic was only two years away from an album called America Eats Its Young.

In a recent, visionary piece for The New York Review of Books, Fintan O'Toole writes about the return of the repressed in American history, the unconverted psychic residues, or "final overflow," of the Civil War and the Vietnam War that in our own time are forcing their way to the surface. "All of this unfinished business has made the United States semidemocratic, a half-and-half world in which ideals of equality, political accountability, and the rule of law exist alongside practices that make a daily mockery of those ideals." The final overflow, the eruption of prima materia into the half-and-half world-this, 50 years on, and layered in scorn and celebration and guitar-scream, is the actual noise of Funkadelic's Free Your Mind ... And Your Ass Will Follow. "This half-life is ending," O'Toole writes. "Either the outward show of democracy is finished and authoritarianism triumphs, or the long-denied substance becomes real."

The minds and asses still unfree. The long-denied substance. It's now or never.

|

|